By: Andrew C. McCarthy

I’m out on the Left Coast to talk about Faithless Execution again today. But at theBenghazi Accountability Coalition, which I chair, we’re closely following the apprehension of Ahmed Abu Khatallah. Here is my statement on it:

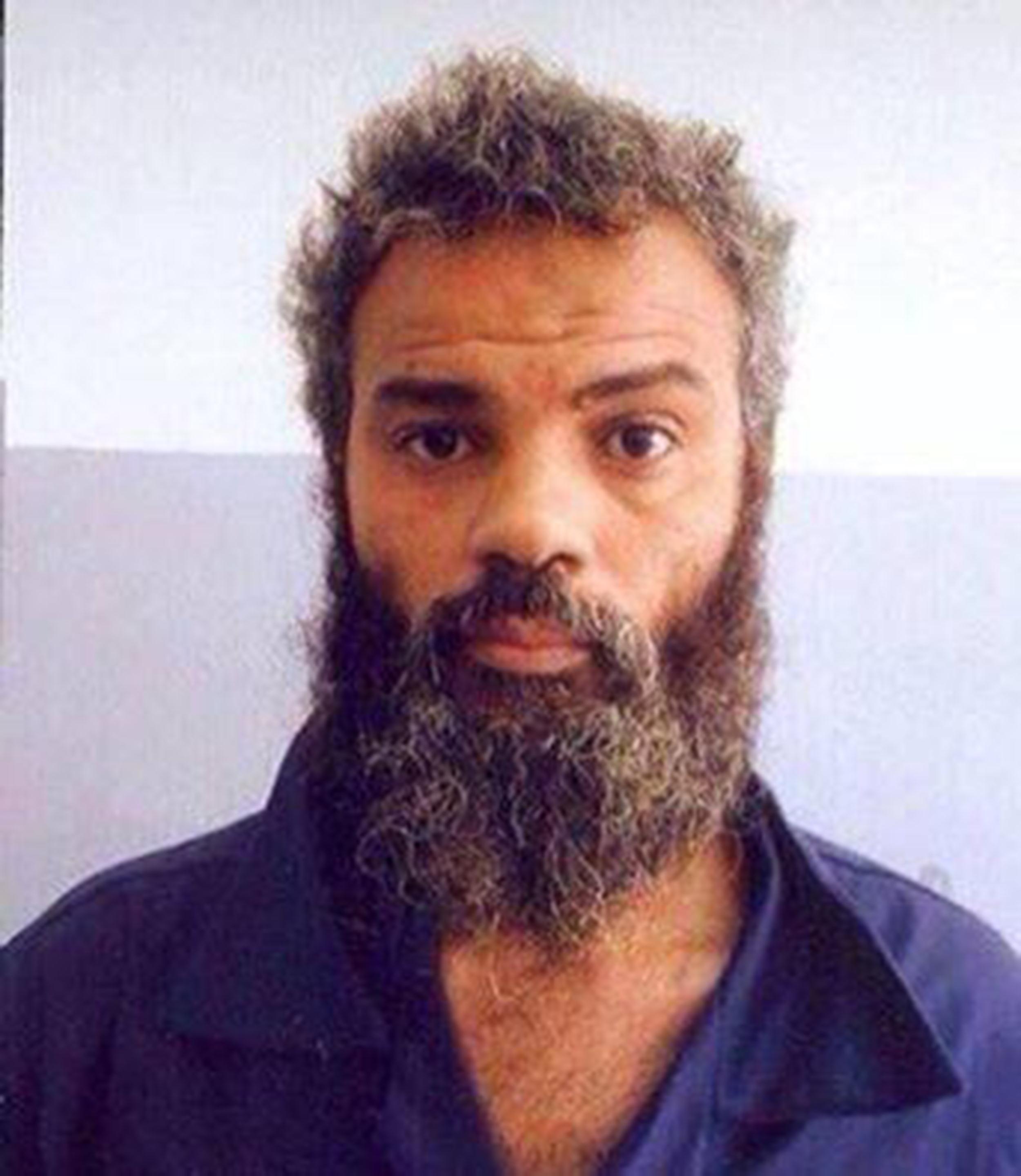

When it comes to the Benghazi Massacre, what the American people want is accountability. The long overdue apprehension of Ahmed Abu Khatallah, who is believed to be one of the jihadist ringleaders responsible for murdering four Americans and wounding many others, is a step in the right direction — albeit a modest one.

It is curious that it took so long to capture Khatallah, who thumbed his nose at our country while meeting with journalists out in the open over the past 21 months. Indeed the curiosity is heightened by the remarkable statement yesterday by former Secretary of State Clinton, one of the chief proponents of the “Blame the Video” meme, that Khatallah — a terrorist operative — had been seen as a culprit by our government since the night of the terrorist attack.

Obviously, a ringleader needs his ring to do the kind of damage our enemies did on September 11, 2012. It is therefore alarming that, although Khatallah is an enemy combatant who killed Americans in an act of war, the Obama administration appears to be treating him as an ordinary criminal defendant. Administration officials have refused to say whether he has been given Miranda warnings. Reports indicate he is on a navy ship headed to the United States, where it appears he may immediately be consigned to the criminal-justice system for a civilian trial with all the due-process protections given to American citizens.

If Khatallah’s interrogation is curtailed because our national security needs are subordinated to the Obama administration’s haste to treat terrorism as a law enforcement matter, critical intelligence about Khatallah’s confederates in the Benghazi Massacre will likely be lost.

At present, there is no reason to reopen the long debate over whether enemy-combatant detainees should be tried by military commission or in civilian trials. There is a five-year statute of limitations on most federal crimes. Moreover, if, as one would assume, Khatallah is regarded as a member of an ongoing terrorism conspiracy against the United States, that conspiracy is ongoing; therefore, the statute of limitations has not even started to run on it yet. The point is: even ifKhatallah were to be treated as a criminal defendant, there is no reason that has to happen immediately.

Khatallah should be detained as what he is: an enemy combatant who has committed acts of war against the United States. Under the laws of war, he may be detained indefinitely so that a competent interrogation can be done, one that is not limited by civilian due process rules that call for the assignment of counsel and that severely limit interrogations.

Whether he is detained on a navy ship, at Guantanamo Bay, or some similar appropriate detention facility for enemy prisoners outside the United States, he should be held outside the criminal-justice system for however long it takes to exploit any useful intelligence he can provide. Intelligence sources often continue to provide useful information for years, as interrogators return to them repeatedly—not just for intelligence about ongoing plots, but for help identifying photographs and voices of terrorists not yet known to the government, and for help interpreting terrorist conversations and documents that are intercepted and seized over time.

There is no reason to rush Khatallah’s interrogation. It would be a travesty if, at a time when our intelligence officials could be acquiring vital information from this enemy combatant by interrogating him about other jihadists who murdered American officials, we are instead treating Khatallah as a civilian defendant and providing him with discovery of our intelligence files — giving him our information instead of getting his, and paying for a lawyer to help him exploit it against us.